Kritiken (863)

Adult Swim Yule Log (2022) (Fernsehfilm)

Some will be lulled by the slow-TV shot of the fireplace, but Casper Kelly, creator of the frantic meta-television short Too Many Cooks, forgot to keep his imagination in check while staring into the flames. Yule Log is a fantastically mercurial comedy with an element of horror and a satirical reflection on contemporary audio-visual work, fittingly made in the environment of Adult Swim’s long-running incubator of bizarre creativity.

Altrimenti ci arrabbiamo (2022)

Why did someone find it necessary to produce a remake of Altrimenti ci arrabbiamo, a film that has attained cult status in certain countries and for certain generations? That question can be answered in one word: Netflix. Yes, the co-producer is none other than the modern equivalent of that 1980s trash factory Cannon Films, but unlike its predecessor, it lacks not only verve and trashy authenticity, but also a genuine filmmaking heart. The online streaming company, whose PR veil of progressiveness and boldness has fallen away to reveal self-serving calculation based on algorithms, is scouring the globe for brands that it can quickly and cheaply exploit and, by evoking both nostalgia and anger, motivate people to subscribe. As in the case of Cowboy Bebop, there was no reason to remake anything here. A remake is a slightly more expensive but still very expedient way to get viewers to watch the original, which will also surprisingly be available to stream on the same platform at the same time. Otherwise, it is interesting to see a young videographer trying to come to grips with the legacy of the original, particularly in terms of style. The original Altrimenti ci arrabbiamo combined the slapstick of early farces with the aesthetics of popular comedies of the 1970s. This time, the filmmakers decided to come up with a furious blend of formalistic chaos (including gratuitous animated interpolations, perhaps in an attempt to give the film more of a comic-book edge) and cheerful, circus-like set pieces disguising the ubiquitous cheapness of the production. To be honest, the original is no cinematic gem and its popularity consists in the fact that we didn’t have American animated slapstick comedies when we were kids, so we were grateful for their Italian live-action equivalent. At the same time, within the boundaries of shallow, popular entertainment, Spencer and Hill had undeniable originality and charm in their clearly readable facial expressions and sweeping gestures, which the remake tries in vain to replicate, falling flat on its face in the process. Furthermore, with its brawls, races and other physical attractions, the film economises to the detriment of the banter and mugging. [screening at the Marché du Film in Cannes]

Ambulance (2022)

On the one hand, it’s regrettable that Bay lost his perversely inflated budgets by liberating himself from the Transformers cash cow and thus has to make formalistic compromises after years of unbridled lavish spending. Bay himself bitterly admits this when he says that some of the CGI shots in Ambulance are “shit”. Still, it’s great to again see this John Waters of the mainstream and Dario Argento of action movies run riot. No one else has the formalistic skills of the master of superficiality. I don’t understand the criticisms that you have to shut down your brain to watch Bay’s films. On the contrary, you can fully enjoy Bayhem only when you switch your brain on and set it to camp mode. Bay doesn't make realistic films and he has no interest in classic narratives. At their core, his films cannot be enjoyed passively, so that viewers are “only” entertained or moved by them. This is beautifully illustrated by a comparison between the original Nordic dramedy Ambulance and Bay’s variation on it. The Danes took the genre elements and strained them through a filter of empathy and levity, thus creating a perfect film for viewers. Conversely, Bay took only the basic premise from the original narrative. He threw out everything civil or (cinematically) realistic and spread out before the audience his world of advertising über-reality and soap-operatic emotions, where everything is turned up not just to eleven, but rather to twenty. As in Zdeněk Troška’s works, in the Bayverse all of the characters express themselves mainly by screaming or barking out simple sentences with the nature of slogans. The less space characters have in the film, the more they are exaggerated caricatures modelled not on everyday reality, but on the manmade illusion of PR and music videos. All of the cars appear to be new and polished, the female protagonist has perfect make-up even in the tensest moments of a field operation and the police are recruited exclusively from the ranks of juiced bodybuilders. Like the aforementioned Argento, Bay doesn’t bother with bullshit like believability and logic, but is only and primarily concerned with making every single shot as stylish and spectacular as possible. And in that respect, Ambulance is an absolute feast. Bay has reached the (for now) peak of his ADHD filmmaking, wagering on one goofily contrived and spectacularly self-indulgent shot after another. In addition to that, he got drones to play with, or rather he got some skilful drone operators, whom he let completely off the leash. Besides the phantasmagorical drone shots and real action with a minimum of digital effects, what’s most amusing about Ambulance is Bay’s attempt to ride the wave of current progressive trends in Hollywood cinema. But because Bay himself is the essence of the term “douchebag”, his version of diversity and representation inevitably takes the form of an absurdly boorish caricature. Bay has simply proven again that his films primarily induce viewers to shake their heads in disbelief. And when properly tuned in, there is wonderful pleasure in that.

Avatar: The Way of Water (2022)

What is the recipe for the success of Cameron’s films? As in the case of Pixar’s top projects and all of Hayao Miyazaki’s movies, there is no secret to it; on the contrary, it is banally uncomplicated, though not simple or obvious. Cameron creates fantasy worlds with the ambition to maximise the viewers’ immersion in them and he achieves this by being absolutely demanding and making no comprises. Cameron’s essential asset as a master director is his complete understanding of the technological possibilities of the medium and his ability to push those possibilities in a visionary way. But what receives little emphasis is the fact that Cameron subordinates to this immersion not only the demands of executing the special effects, but primarily his formalistic signature. He doesn’t create money shots, fool around with the camerawork or editing, show off with flashy long shots or otherwise let the film exhibit itself to the audience. When he goes for a slow-motion shot, he does so in the interest of working with the dynamics and build-up of the whole sequence, not with the aim of making a cool picture. That doesn’t mean that he doesn’t set challenges for himself. His films contain a lot of difficult shots and each of his projects is actually a major campaign with the objective of conquering new territory for cinema as a medium of illusion. But, again, all efforts remain subordinate to the audience’s immersion in the given world he has created. This maxim also guarantees that the narrative isn’t cluttered with anything that would break the fourth wall, whether references nodding at fans or characters and artefacts that serve only as intrusive advertisements for associated merch. Unlike Star Wars and the Marvel movies, Cameron’s films don’t offer corporate-calculated webs of stories that would lend themselves to fandom fetishisation. Instead, Cameron simply creates fictional worlds that entice viewers with their fantastical nature and the promise of their settings and characters. Cameron himself says that his screenwriting process comes from two directions. On the one hand, there are the characters and their relationships. On the other hand, there are the specific scenes and settings that Cameron would like to see. Writing the screenplay then involves coming up with motivations and peripeteias that connect these two pillars causally and logically. Then, of course, there is Cameron’s own imagination, which shapes the particular worlds. And that’s all; there is nothing else behind his success (well, except for effective PR, which in turn relies on the potential that Cameron creates). It then invites further reflection on what it says about the state of blockbusters and Hollywood as a whole when the above is not the norm but a celebrated anomaly. ______ In light of the above, the only weakness of Cameron’s films is his screenplays. Or perhaps it’s only the perspective of viewers who aren’t completely captivated by them. Compared to the first Avatar, the narrative shifts in the sequel may not sit well with some viewers. Conversely, some will be irritated by the excessive similarity between the two films and the repetition of motifs. Still others will have an issue with the apparent lapses in logic (even if they are transgressions against the opinions of the respective viewers and not against the rules of fiction). Other people won’t be able to get past the wall of their own cynicism and accept the new-age environmental ethos, naïve mythmaking, post-colonial romanticism or Cameron’s characteristic melodrama. Personally, I was saddened mainly by the evoked impression that I had already seen several times. For one thing, Cameron again builds on the first film’s love story with the story of a family on the run and a coming-of-age motif, just as he did with Terminator 2. The story of parental love that turns into anxious criticalness and the necessity of giving adolescents their freedom regardless of what mistakes they make as a result because they can grow only by making those mistakes fortunately remains universal and fundamental enough not to seem derivative. Furthermore, its likable in that it irritates the parents in the audience and appeals greatly to younger viewers. Apart from that, however, memories of key sequences in Titanic and The Abyss inevitably creep into one’s mind at particular moments in the film. On the other hand, the idea that Cameron is merely ripping himself off can be quickly dispelled by recalling the work of George Miller, who also works with variations on certain motifs in the Mad Max films. Cameron also uses similar situations simply because he likes them, knows their dramatic potential and enjoys recreating them. ______ After all, personal passion and imprinting one’s signature on a film are essential attributes of a director’s work. Cameron most clearly projects into his films his often mentioned fascination with strong women and warrior mothers, as well as his fascination with the undersea world. With respect to the latter, the second Avatar is perhaps his most inward-looking project since The Abyss. In multiple storylines, he expresses the desire to merge with that alien world which is so close, actually within reach, but the limits of the human body constantly make its strangeness and unattainability felt.

Bullet Train (2022)

Bullet Train can be criticised for a lot of things, but it can also be enjoyed for the same reasons. Here we have Japan literally on a high-speed train together with a furious pace and non-linear narrative that rather serves to divert the viewer’s attention and mask the screenplay’s shortcomings, as well as the simulation of depth and reach typical of the source material’s author, Kōtarō Isaka. Unlike Japanese adaptations of Isaka’s novels, here the motifs of interconnectedness, luck and fate do not evoke wonder and pathos, but are ground down into superficially entertaining attractions. Bullet Train also works with Tarantino-esque characters, i.e. absolutely unrealistic genre characters that stand out due to their exaggeration, stylishness and grounding in pop culture. Based on the described principle, Tarantino and some of his disciples create sophisticated, powerful and seemingly well-thought-out gangsters and killers that, in the best case, transcend the level of the wet dream of fictional perfection and become semi-divine ideals that viewers admire. In Bullet Train, however, they just remain unrealistic, amusing puppets with one cartoonishly exaggerated and endlessly repeated attribute. Then we have the action scenes, or rather their choreography, which was at the forefront in previous 87North (or 87Eleven) productions, drawing attention to itself through spectacular physicality, difficulty of execution and revolutionary ingenuity. This time, the action is rather in the background, always primarily in the form of slapstick gags connecting the individual plot sequences. Whatever overarching term we use for the film’s described tendencies – bastardisation, anti-sophistication, dumbing-down, assimilation or Hollywoodisation – this is what gives Bullet Train its charm and effectiveness. The film absorbed into itself every possible trend of previous years and even decades that had been valued by overly clever fans, cinephiles and devotees of alternative niches, and strained them through the mainstream filter to create a universally accessible form. It will inevitably be derided by the elites because it is not like the perfect forms that they appreciate, but it will make Bullet Train a popular box-office hit. After Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw, Leitch’s subsequent project evokes the middle-of-the-road works of Hong Kong cinema’s golden era, which comprised chaotically disparate variety shows blending together a multitude of emotions and genre positions, and where the audience’s attention was constantly drawn to various attractions, including action escapades and cameo appearances by popular stars. If we recall that David Leitch and his contemporaries are great admirers of Hong Kong movies, it’s possible to see this not as a coincidence, but as a concept.

Der gestiefelte Kater: Der letzte Wunsch (2022)

In 2001, DreamWorks released Shrek, whose box-office success had fatal consequences for mainstream animation. Whereas Pixar promised to advance the technological and expressive means of computer animation with every new project and to come up with new worlds and stories, Shrek demonstrated that it sufficed to have a broadly funny screenplay with smart-ass pop-culture references and viewers wouldn’t really give a damn about the quality of the animation. Sony Pictures Animation changed the game in 2018 with its animated Spider-Man and even the complacent bosses at DreamWorks understood that viewers would henceforth no longer be satisfied only with bubble-gum cartoon characters illustrating verbal jokes. Alongside The Bad Guys, the new Puss in Boots boasts a visual refresh that greatly benefited from the stylistic facelift. Though the screenplay rather exhibits the characteristics of direct-to-video sequels (few characters and settings, a straightforward narrative that vaguely benefits from the world previously presented, a repeat of the structure and concept of the previous instalment of the franchise), the animation elevates everything to the level of a grandiose spectacle. For one thing, instead of the long-utilised pseudo-realism, where every single hair on an animal’s coat and photorealistic reflections and shadows played first fiddle, the overall visual concept takes on the stylisation of tempera paintings, though not on a large scale, but rather in micro dimensions. Thanks to this, small details and surface textures can still stand out, but the overall impression is miles away from the toy-like artificiality of classic computer animation. The action scenes formalistically take on the expressive vocabulary of anime, with spectacular poses, rapid cuts and the contrast of slow-motion and, conversely, accelerated movement suggested by quick jumps between key images and individual poses. Though the animation here does most of the heavy lifting when it comes to attracting the viewer’s attention, it is not divorced from the whole, as it remains firmly symbiotic with the screenplay, the foley effects and – in the case of international releases – the dubbing. This cohesion is most evident in the imposing character of the antagonist wolf, which is a magnificent audio-visual feat in and of itself.

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

I thought such an unrestrained eruption of creativity was possible only in animation and I’m terribly glad that Dan and Daniel have shown me how wrong I was. On the other hand, no one has ever approached the medium of film with such hyperactive playfulness as they have. While their meta-work is essentially cinematic (in terms of the story being told, the narrative processes and the references), it also personifies the internet in its Web3 phase, with all of its fascinating beauty, pioneering potential, non-linear hypertextual nature and terrifying intangibleness far beyond the possibilities of a single person’s perception. After all, the creative approach of the disparate and yet extraordinarily symbiotic creative duo of Daniels fulfils the principles of decentralisation and blockchain interconnectedness. Everything Everywhere All at Once continues on the path marked out in the field of feature films by the animated movies Spider-Man: Parallel Worlds and The Mitchells vs. the Machines, but its concentration of online popular creativity, both audio-visual and graphic as well as narrative, is breathtaking and rocks the senses by adapting them to the much more production-intensive format of a live-action film. Perhaps it is thus not a coincidence that everything here ultimately revolves around family, though in a completely different and wonderfully imaginative style in terms of family dynamics in relation to the traditional roles of villains and heroes who have to evolve in order to overcome evil. In addition to that, Everything Everywhere All at Once gives Michelle Yeoh the role of her life, in which she puts the experience of all of her previous on- and off-screen roles to good use.

Falcon Lake (2022)

Charlotte Le Bon came up with the brilliant idea of depicting teen romance through the formalistic lexicon of horror. Because what is more terrifying, more monstrous and more unsettling than growing up, shyness, the insecurity that comes with persistently recurring feelings and pretending to be cool in front of others? This idea in itself could have been enough, but Falcon Lake transcends it in the way that it captivatingly observes and then delicately projects onto the screen the intense excitement, worries and awkwardness of one’s first great teen love, when childhood naïveté and fragility are combined with the flood of hormones coursing through one’s body. At the beginning, the slow pace and genre-appropriate building of tension may seem out of place, but when you accept these aspects, the film will not only get under your skin, but also into your heart and may even drag up old wounds and indiscretions. Diving below the surface of Falcon Lake is thus both fittingly painful and romantically beautiful.

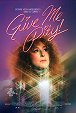

Give Me Pity! (2022)

While watching Give Me Pity!, I often thought of giallo – not as a direct inspiration for the film, but as a parallel reference to grasp this highly atypical work. We can say about the boldest giallo films that their crime context and widescreen compositions with a distinctive colour palette invite a creative formalistic rampage beyond the boundaries of the ordinary and the limits of realism. In principle, Give Me Pity! uses the framework of the TV variety-show format and the 4:3 aspect ratio of old beta television cameras for the same purpose. In its adoption and subversion of the television format, as well as its remixing, disruption and purposeful deconstruction, Amanda Kramer’s film can evoke the live-action works of Adult Swim. However, it remains entirely distinctive and unique, because the intention here is not limited to stoner absurdity. Through the central monumental one-woman-show (with the help of three episodic characters and three dancers), it is actually about the murder of oneself, or rather one’s own distinctiveness on the road to fame in predefined pigeonholes. Through grotesque stylisation, the film expressively presents the process of role-playing for fame within the adopted bizarre boundaries of the target media, which is inherent not only in the film’s central character, but also in all of the people who, through their public alter egos, supposedly live out their own daily prime-time shows on social media.

Hetki lyö (2022)

It’s funny in Finland, or Finns in Spain as wasted vagabonds who constantly drink because alcohol is cheaper and more available there than it is in Finland. This could, and perhaps should, have been something between Guy Ritchie’s early gangster films and John Waters’s adoration of the white rabble. Except that the film is tragically lacking in pace and humour to be Ritchie-esque and it falls short of Waters’s style because instead of his underground authenticity, Hit Big revels only in superficial melancholy towards the degraded mainstream pop culture of the past and, furthermore, its white-trash stylisation comes across as mechanical and forced. Unlike all real white trash, the central protagonist never runs his hand through his exquisitely styled hair so as not to smear his carefully applied make-up. But as an spectacularly ugly bastard child of grant initiatives for European co-productions, it’s a likable piece of work at its core.