Kritiken (862)

Godzilla Minus One (2023)

Godzilla Minus One = Japanese Rambo II. Stallone’s all-American hero of his time nullified the historical wrongs of a lost war, admonished the illusory powerholders controlling a ruthless system and restored pride to veterans by enabling them to fight a winning battle for themselves, out of uniform. The Japanese just had to wait many more decades to do the same for themselves. In the hands of Yamazaki, the Japanese master of spectacular melodrama, the latest prequel/reboot/remake/whatever, simply another way to squeeze the last drop out of the brand, becomes such a crystal-clear resuscitation of classic formulas and kitschy emotions that even Top Gun: Maverick is green with envy. Whereas Tom Cruise successfully remained in the realm of functional pathos, Godzilla and its human fellow travellers spectacularly dive to the greatest depths of heavy-duty cringe. In the end, however, the supposed detached humour and derisive distance of the audience are purely illusory when you realise that you were royally entertained by this film, which by Hollywood standards is a low-budget showcase of embarrassingly exaggerated clichés and gaudy kitsch. ___ Nevertheless, the new film has a disturbing core that mirrors a basic principle of the rising conservatism in Japan and beyond, i.e. the need for an easy substitute lightning rod for negative emotions, as far removed as possible from the real pressing issues of the status quo. In Godzilla Minus One, we have a properly dehumanised and alien monster instead of the maximally humanised Godzilla/friend from the franchise’s cuddly era, which despite the would-be adult smartasses remains the franchise’s best, most entertaining and, mainly, most culturally mainstream phase. On the other hand, we can say that Godzilla shows itself to be a real timeless hero of Japan, because in the decades that it has spent at the top of Japanese pop culture, the lizard knows that hard times and wounded national pride sometimes don’t require the truth. Sometimes people deserve to be rewarded. And so, from time to time, the cute puppet has to put on some CGI armour and for a moment become the hero that the audience doesn’t deserve, but the one it needs. Because it can endure that. Because it’s not just a hero. It is a silent guardian and a watchful protector. Dark [insert Godzilla roar].

Under the Skin (2013)

The Fifth Element from the far side of the world, and an eerie cryptic metaphor about gender dynamics, a double-edged form of unrestraint and the violent nature of human communication.

Der Junge und der Reiher (2023)

The older Miyazaki gets, the less literal and linear his work becomes, the less regard he has for classic narrative concepts and the more he makes films solely for himself without any regard for others. And thanks to that, each of his new works that we have the good fortune to see for the first time is that much more fascinating and unique. So, it is time that we stop recounting which elements and motifs that his latest film has in common with those that came before. The most beautiful thing about Miyazaki’s films has always been that rare opportunity to forget about everything that we are accustomed to in run-of-the-mill audio-visual media and to let ourselves be carried away by the creator’s unique vision. Not only does one limit the degree of amazement by relating this film to the master’s previous work, but doing so also diminishes the distinctiveness of the film itself, which requires an open mind. Let’s also acknowledge that the title, The Boy and the Heron, originated as a meaningless placeholder in the heads of international distributors, who didn’t know what to make of the original title, which didn’t fit into any established categories. Let’s thus call the film by its real name: “How Do You Live?”. The original title pays tribute to the book of the same name, which was essential for the adolescent Miyazaki and even appears in the film. However, the filmmaker did not adapt it, rather only using its title as an allusion, as well as for a semantic framework for not only his new film, but for his overall work. Just as the concept of time fades away in the narrative and the elderly characters appear in their youthful form and the generations of a single family can come together at the same time, Miyazaki uses the question in the original title of his film to speak both to himself and to us about his own past and present. In his latest work, the filmmaker, who has devoted his entire productive life (which, in the case of the workaholic octogenarian, means to this day), uses another such narrative to give us an expressive look into the inner life of a young man buffeted by trauma, loss and apprehension about the life that lies ahead of him. In that inner self, new worlds that simultaneously exude uplifting boisterousness and the weight of inevitability are created using the basic building blocks of reality and fantasy, cemented together with emotions. Together with the titular question of how we will live in the face of an oppressive world, Miyazaki shows us through his protagonist how he himself coped with growing up in the shadow of war and the death of his beloved mother. Using the words of today’s audio-visual media, we could say that Miyazaki’s new film is the magnificent peak of his filmography (so far), as well as a meaningful prequel to it. In this film, Miyazaki presents to us the duality of beauty and terror, love and anger, and simply life and death, as he has done throughout his career so far. Each new Miyazaki film is like a half-read book left in the middle of a shelf by a missing uncle who went mad from reading countless books. Those films’ renown precedes them and evokes in us a feeling of awe at being in contact with something that will inevitably go beyond us, as well as foolish concern as to whether the films will live up to expectations. Therefore, we approach them only cautiously and sometimes, to our own detriment, we refuse to give in to them. But it is enough to break through the first wave on the horizon and let it wash away all doubts, and then just peacefully sail with an open mind aboard the narrative, which is held securely in the hands of the greatest master of cinema. And yes, again, it is a journey that overwhelms us with imagination many times, but it is also a journey from which we will always have memories of those peaceful moments when we realise that we are suddenly as calm and collected as the characters that we are watching. There is nothing more precious, more terrifying, more beautiful, more agonising, more turbulent or more comforting than each new Miyazaki film.

Big Game - Die Jagd beginnt (2014)

The filmmakers’ ambitions were apparently limited to trying to combine children’s adventure stories with a mountain-set action thriller in the style of Cliffhanger, without concerning themselves with the idea that it should hold together or fulfil some smart-ass grown-up requirements. Because who would bother with the logic of time, space and the laws of physics when you can just come up with some cool shots. It’s a pity that they didn’t have the resources to go all out with those shots, so the result is kind of half-baked. And that is a terrible shame, because the film has real heart, but it’s buried under a heap of dead weight. I’m not surprised that film nerds are howling, because this is exactly what they hate – a movie with a bombastic promo that twists its potential for sullenly cool arrogance into gleefully childish nonsense.

Das Erbe oder: Fuckoffjungsgutntag (1992)

Despite the obtuse criticisms of the time, Věra Chytilová did not create a Troška-esque farce. Nor did she lose her sound judgment or sell out to commerce. However, contemporary and, unfortunately, later viewers were unable to tell the difference between satire and communal comedy. Chytilová was the only one to not go for superficiality, but instead created a timeless and unflattering – and thus all the more chilling – freak show in which she exposed Czech society drunk on a feverish vision of wealth, freedom and power in all its nakedness. Unfortunately, an inherent drawback of every satire is that some people see it as a confirmation of their own values and preen in front of the mirror that has been set in front of them instead of being horrified by what they see. And particularly the image reflected in The Inheritance is utterly, terrifyingly monstrous, though it is also a meaningful statement on more than just its own time and the deterioration of its values.

Curse of the Queerwolf (1988)

A typical Pirromount product or one-man-band production by Mark Pirro, who – like many other bumblers of the late 1980s and early ’90s – found an outlet for his naïve nonsense on the perpetually insatiable video market. We can see Pirro and his fellow travellers as predecessors of the supposedly millennial mockbuster trend. Or rather, they show us that the trend of ridiculing and parasitising the mainstream is not unique to today’s audience, springing from memes and parodies on social networks, but that it also thrived on the curiosity of movie fans as far back as the VHS era (whereas in earlier decades the trend was fed by parodic porn productions and softcore dreck for grindhouse cinemas). But instead of bullshit CGI, they were armed only with desperate humour and superficial allusions. Curse of the Queerwolf is an illustrative and, to a certain extent, the best example of Pirro’s creative style. Its foundation is the oddball premise indicated in the film’s title, which in itself offers the promise of absurd entertainment at the expense of familiar formulas. A handful of scenes that perfectly paraphrase well-known, thematically related classics (here specifically Deliverance, The Exorcist and, naturally, all kinds of werewolf movies, particularly An American Werewolf in London) are derived from that premise. But in practice, they’re not enough to cover a feature-length runtime. Pirro thus fills out the rest of the film with random insipid jokes, which share with the film’s main storyline only an identically varying level of stupidity ranging from embarrassing to imaginative. Where the titular queer motif is concerned, Pirro doesn’t address any issues of correctness, but simply uses whatever jokes that happen to come to mind. Thanks to that, it remains up to the audience whether they want to see Curse of the Queerwolf as a progressive mockery of conservatives and gender stereotypes or as a bunch of homophobic clichés, or just as an insipid farce.

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

The American interpretation of the banality of evil, where “banality” is synonymous with the everyday and the ordinary, but it is not readily apparent. Scorsese needs these three and a half hours so that he can depict, with maximum disturbing effect, the paradoxes and absurdities in the actions of people who, with the support of institutionalised racism and under the banner of their own truths and idealised values, were able to live side by side with those whom they killed. Two aspects stand in opposition to each other. On one side, there is the mythology of a nation that is being corroded by adapting to an imported lifestyle, or rather to a foreign mythos of prosperity. The tragedy of the Osage consists in the fact that they tried to adapt to a foreign mythos, but from the perspective of the white outsiders, that mythos was (and still remains) meant only for themselves and not for anyone else. On the other side, we have a stubborn self-centredness underpinned by an imagined right to prosperity in a land of unlimited opportunities, which in practice means that it can be seized by any means at the expense of others. The narrative consistently makes us aware that evil does not consist in some sort of moral gymnastics that the individual uses to justify his or her opposition to good. On the contrary, the essence of evil consists in absolute rational ignorance with respect to anything foreign, including morality. Essential support for this is provided by the instilled roles, models and ideals that one has to fulfil, because the effort to fulfil them helps one not to see anything else. Fortunately, however, there is a third side, represented not by the local authorities, but by those of the state, which in Scorsese's typically idealistic vision are completely immune to the corruption and temptations of the world around them, because they are built specifically for the purpose of fighting evil. Thanks not only to the presence of DiCaprio, Killers of the Flower Moon is a reprise of The Wolf of Wall Street, in which Scorsese portrayed the perversity of egocentrism and opportunism so spectacularly that his film became a materialisation of the dreams of numerous assholes and a representation of what they should aspire to. This time, in the acting itself (from DiCaprio's clumsiness to DeNiro’s adaptation of Donald Trump’s facial expressions) and in the purposefully slow pacing, he deliberately takes care to ensure that his view of America’s values cannot in any way be misappropriated in the furtherance of those values, though the effort is ultimately futile, because nothing external will break the convinced racists and mammonists.

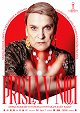

Přišla v noci (2023)

Hell is other people. And that’s all the more true in the case of your own family, because you can never escape from it, which is also due to the fact that you carry your family inside yourself forever. Jan Vejnar and Tomáš Pavlíček have made a brilliant home-invasion horror movie in which the terrifying (and suffocating) substance of familial relationships takes the place of the usual genre elements. The reactions in the cinema, filled with heavy, painful sighs, sheer terror and desperate laughter of those longing in vain for relief, provide confirmation of how the filmmakers brilliantly captured the details of psychological terror not only of the maternal variety, but also of the general variety extending one way across the chasm between the generations. Their film’s power lies in the devastatingly accurate casting, which fills out the screenplay based on internally observed and analysed feelings and their triggers, which are embedded in the screenplay with frightening precision and devastating authenticity, whether that involves lobotomising solicitude, crushing egocentricity or merely the exhausting, overly clever wisdom of the elderly. She Came at Night also excels in how it manages to acutely thematise the core of its genre, i.e. the home itself, from the perspective of its importance for the central characters, as well as with respect to how its violation impacts the characters. Of all the elements that the filmmaking duo put into their work, the most terrifying is the fact that they don’t demonise the central monster, but rather point out that each of us has the potential to become such a monster. The fact that the monster is not capable of self-reflection and, because of that, sees herself as a misunderstood victim gives She Came at Night an additional chillingly meaningful level that goes beyond the boundaries of the microcosm of one family, revealing an unsettling general truth about the core of numerous problems in society.

The Big Lebowski (1998)

Not all superheroes wear capes – some wear bathrobes. When I grow up, I want to be like the Dude. Until them, I will imbibe his wisdom and a White Russian during the regular annual review of the holy scripture of Dudeism on New Year’s Eve at the Aero cinema in Prague. ——— Otherwise, The Big Lebowski is not only grand entertainment that never loses its appeal, which is thanks to the brilliant casting of an outlandish bunch of likably oddball characters, but it is also the most cunning and most clever neo-noir film that Joel and Ethan Coen have come up with.

Falcon Lake (2022)

Charlotte Le Bon came up with the brilliant idea of depicting teen romance through the formalistic lexicon of horror. Because what is more terrifying, more monstrous and more unsettling than growing up, shyness, the insecurity that comes with persistently recurring feelings and pretending to be cool in front of others? This idea in itself could have been enough, but Falcon Lake transcends it in the way that it captivatingly observes and then delicately projects onto the screen the intense excitement, worries and awkwardness of one’s first great teen love, when childhood naïveté and fragility are combined with the flood of hormones coursing through one’s body. At the beginning, the slow pace and genre-appropriate building of tension may seem out of place, but when you accept these aspects, the film will not only get under your skin, but also into your heart and may even drag up old wounds and indiscretions. Diving below the surface of Falcon Lake is thus both fittingly painful and romantically beautiful.