Kritiken (935)

The Fall – Tod in Belfast - Season 3 (2016) (Staffel)

...and justice for all? I can understand the disappointment of those who expected another thrilling game of cat and mouse, instead of which they got Paul Spector’s six-hour anamnesis. At the same time, however, I appreciate the creators’ courage to take a different approach (more dialogue, less action, a slower pace) and stick with it from start to finish (with a constantly high level of directing and acting). The same is true for the series as for its first episode – it begins where other narratives end and goes into the smallest details about the men and, especially, the women Spector has affected and the procedural steps associated with verifying his medical condition, which would take only a few minutes elsewhere. The result is (psychological) believability and gradually rising uncertainty about what awaits us once the final layer of Spector’s personality has been revealed. The focus of the series thus essentially remains on uncovering the murderer’s identity and intentions, only this time, instead of suspense, it raises questions relating to morality, upbringing, parenting and justice (how to deal with a person who may not know that he is a murderer). Spector serves as a mirror of the fears and insecurities of the other characters, who are connected to him in various ways and share responsibility for his condition and the safety of those around him. In the finale, the others are paradoxically far more unstable than Dornan’s chillingly calm psychopath (one became an alcoholic, someone else is overcome with loneliness), who retains some control of the situation until the final moments. Despite the initial reservations, this turned out to be a meaningful and satisfying, if not breathtaking, conclusion to the series, which is extraordinary for, among other things, its even distribution of strengths (and attention) between the sides of good and evil.

Jack Reacher: Kein Weg zurück (2016)

Jack doesn’t waste time. Before the movie even starts, he manages to pacify two guys and bring two more to justice before the opening credits, during which he manages to set up a date with a woman he has only just met. Roughly the first third of the film is a terrific lesson in narrative economy. Neither the characters, who take action instead of making unnecessary speeches, nor the viewers have time to breathe. The only thing that slows Reacher down is the second woman who enters the story, because of whom the protagonist must not only flee from justice and search for the real villain, while at the same time acting as a responsible father figure and giving instructive advice, which does not fit his type of pulp hero at all. Furthermore, the relationships between the characters lack the necessary dynamics due to their weak development and the bland actors who portray them (though the characters are allegedly one of the main reasons the filmmakers chose Never Go Back over approximately twenty of Child’s other books as the source material), so you will have plenty of time to ponder the predictability of the mediocre plot in comparison with the brisk beginning. If you try, you can easily guess how a given scene will turn out. If you try a little harder, you will have no trouble deducing how the whole film will end. As a fine bonus, I welcome the fact that the relationship between Turner and Reacher remains on a professional level (its nature is nicely demonstrated by the fact that neither of them addresses the other’s semi-nudity as they inspect their ragged wounds). The only narrative betrayal, which partially justifies the weakness of the relationship storyline, comes at the very end, when it is necessary to clean the slate and the restore the status quo so that the franchise can continue without disruption. In comparison with the more diligent McQuarrie, Zwick merely fulfilled his commission. A cruel price is paid for this particularly by the interchangeable, quickly and vaguely edited action scenes (only the sound effects provide any kind of orientation), none of which comes close to the bathroom brawl or car chase from the first film. In an era of recycling tried-and-true franchises and making exorbitantly expensive comic book adaptations, I appreciate the fact that someone is taking on a mid-budget 1990s action thriller in which the plot plays a bigger role than spectacular CGI sequences. It may not be so apparent from that how little effort most of those involved put into the attempt to make something worth remembering. Two days after the screening, I’m not sure whether I saw a new Tom Cruise movie or commercials for Washington’s public transportation system and the sports cars that American cops drive. The first Jack Reacher made the most money outside of cinemas (DVD, Blu-ray, VoD). The second one seems to have been intended from the start as a movie to be watched on trains and planes. And that’s a shame. 65%.

Asche und Diamant (1958)

When the winners lose... Ashes and Diamonds is a very slow (partly due to the length of the shots), very disillusioning, very deep dive into the atmosphere of the time when one war ended and another began. Besides knowledge of the social and political contexts (a communist appropriates everything, with the exception of his son), Jerzy Wójcik’s brilliant camerawork is what forces us to think. No showing off, minimal movement, great depth of field, well-chosen angles. The shot with Christ turned satanically upside down and the subsequent pan to the place with an open coffin in the background is worth a thousand words. In the final part of his war trilogy, Wajda plays with contrasts (fireworks and death, dark blood seeping through a white sheet), subtly referencing his own work (Maciek wears dark glasses because of his time spent wandering in the sewers) and that of others (the film’s title is taken from Norwid’s poem of the same name, the final polonaise stylised along the lines of Stanisław Wyspiański’s play Veselka, which Wajda filmed in 1973). Thanks to the artful cool of Zbigniew Cybulski, the torn romantic hero (abrupt transitions from tragic gloom to cheerfulness) who likes to play with fire (literally), neither the the slowly escalating, dreamy romantic storyline nor the brief encounter with the diamond amidst all the ashes is superfluous. Only the closing scene of suffering seems slightly forced. 80%

Ich, Daniel Blake (2016)

I, Daniel Blake starts out as one of Loach’s most powerful films. The octogenarian standard-bearer of British left-wing cinema directs with admirable precision and economy, though it may seem that he is primarily trying not to get in the way of the actors’ work. He gradually interconnects the protagonist’s story with those of the supporting characters (Katie, Chino), thus inconspicuously pointing out how important people like Daniel Blake, who don’t live solely for themselves, are in uniting a community. As if by accident, the camera sometimes takes in anonymous people waiting at an office who find themselves in a similar situation as Blake, thus drawing attention to the widespread nature of the issue being examined in the manner of neorealist films. Also, the choice of setting on both a larger (Newcastle) and smaller scale (Blake standing incongruously in front of a display window with luxury goods) reveals the director’s sensitivity and talent for conveying meaning in a slightly roundabout way. Despite the melancholy subject matter, the film is greatly helped by humour from the beginning. Dave Johns, who otherwise makes his living as a stand-up comedian, has precise comedic timing and I easily could have spent an hour and a half listening to his increasingly clueless communication with robotically thinking officials. But as Blake’s humour abandons him, Loach also loses his ability to maintain distance and starts pushing the situation to extremes. I have no doubt that he proceeded based on field research and interviews with unemployed people, but in this concentrated form, the unhappiness and desperate behaviour occurring all at once (the freezing children, the food bank, Ivan, vandalism, the final scene) are unnaturally excessive. The attempt to support the thesis that bureaucracy is harmful to both mental and physical health gradually takes precedence over perceptiveness toward the characters and the film becomes exceedingly literal in its attack on the system. It suddenly becomes too obvious what the director is reaching for and thus harder to accept. Of the recent dramas about dehumanised and dehumanising capitalism, I, Daniel Blake, despite all of its qualities, thus remains in my view a few steps behind the brutally blunt The Measure of a Man and the more well-constructed Two Days, One Night.

Toni Erdmann (2016)

“Are you even human?” Laughter through tears. Maren Ade’s third film is a sad costume comedy whose characters are most exposed thanks to the masks they wear. Their addiction to living in solitude and by their own rules both divides and unites Winfried and Ines. We see them alone for a substantial part of the film, at moments when the relieving effect of laughter reverberates and the awareness of a missed opportunity and irreversible estrangement returns. Unlike many contemporary American indie comedies and series, an awkard feeling is not an end in itself. Besides laughter, it evokes sympathy and relates to the key theme of humiliation and inadequacy. The characters feel this inadequancy with respect to each other, themselves and the world they live in. The film does not take the side of either of the characters, which is reflected in its structure and in the way situations that seem like a victory for Winfried suddenly turn in Ines’s favour. We spend roughly the first hour of the film with Winfried, who then suddenly disappears from the narrative with no promise of whether we will see him again. We then stay by Ines’s side for a while until Winfried’s reappearance, which is as unexpected as his departure. During the rest of the film, perspectives alternate in the manner of passing a baton. A scene begins with Ines, in whose life Winfried/Toni suddenly appears (sometimes indirectly, through his crafty way of relating to the world – see the erotic hotel scene) and with whom we stay even after Ines leaves the scene. The ease and unpredictability with which Ade combines comedy with tragedy, intimate drama with an account of socio-economic relations in globalised Europe is not the result of happy accidents and improvisation à la Dogme 95, but of precise work with editing and mise-en-scene, which prepares us in advance for some of the next scenes while creating false expectations. Thanks also to the masterful directing, we experience uncertainty, wonder, sadness, joy, humiliation, rejection, acceptance and catharsis at the same time with the characters, whom we don't want to leave behind after 160 minutes not because we feel good with them, but because we have so much in common with them. I’m sorry about only one thing: it is unlikely that I will see anything better (equally unpredictable, funny and sad) this year. 95%

The Girl on the Train (2016)

Just as when reading the novel on which The Girl on the Train is based, it is impossible to avoid comparisons with Gone Girl. Both films have noirish, bleak visual stylisation (in Fincher's case, that’s the director’s signature; in Taylor’s, it’s rather an imitation), both depict marriage as a life-threatening game filled with manipulation, lies and hypocrisies (with a cynical sense of detachment and ironic distance from the characters in Gone Girl, but in all seriousness in The Girl on the Train), and both films alternate between multiple narrators (with greater sophistication in Gone Girl). Compared to the slightly misogynistic Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train is more explicitly targeted at adult female viewers, who are encouraged through Rachel’s story to rely on themselves rather than on what they are told or what others want for them. Especially men. ___ As in the book, the final reversal of the roles of victim and offender is a tribute to the emphatic pro-woman cri de coeur, which greatly degrades the impact and sheds doubt on the meaning of the film’s portrayal of an alcoholic woman. Built more on strong acting performances than on narrative games, the film is largely conceived not as a crime thriller, but as a psychological study of an internally insecure woman in search of her lost (self-)confidence. The ending, which unlike the book contains a needless epilogue, suddenly negates this feeling of shame and guilt, intensified by the excellent Emily Blunt throughout the film. As in many of Hitchcock’s thrillers involving the transfer of guilt, the perpetrator was someone other than the film had previously indicated, which in this case, however, serves to resolve only the crime aspect of the narrative, but not the psychological dimension, which comes off as unsatisfying. ___ Thanks to the graphic continuity of the shots and precisely timed editing, Taylor succeeds in fostering the impression of fluidity and interconnectedness of the individual segments of the narrative, or rather of the individual narrators. Flashbacks showing various distant episodes from Megan’s life intensify the suspense with respect to what actually happened. Like Rachel, with her memory affected by sipping vodka, we know only fragments of reality and we have to continually add to and adjust the overall picture on the basis of new information. Like the protagonist, we also mistakenly infer who we are seeing in some of the images based on the available context. The unreliable narrative thus does not serve as the screenwriter’s calculated attempt to deceive the viewer, but is organically connected with the protagonist’s mental state and cognitive abilities. As a result, The Girl on the Train is a compact and focused film, most of whose shortcomings (the mishandled ending, lack of detachment, occasionally melodramatically forced sense of tragedy) stem from the book’s premise or are associated with the audience’s expectations (it’s not a thriller, but a drama). If you see romantic relationships as a cynical comedy that sometimes bring a smile to your face, Gone Girl will probably remain your favourite relationship movie. If you prefer a more tragic approach, The Girl on the Train may suit you better. 80%

The Fall – Tod in Belfast - Silence and Suffering (2016) (Folge)

If this weren’t an episode of The Fall, it could have been a highly above-average episode of ER. It is still a first-class procedural, overwhelming viewers with information that they don’t need to know but which contributes to the realistic effect. We don’t follow the investigators at work, but the heroes who come after them – the hospital staff. Serious moral issues are still addressed (death vs. justice, providing aid no matter what the person lying before you on the operating table has perpetrated), Stella’s ambivalent relationship to Spector remains the centrepiece of the narrative, and the compactness of the narrative is still breathtaking (only the hallucinations with the hackneyed light at the end of the tunnel are somewhat off the mark). However, doubts are raised as to whether it wouldn’t have been better to end on a high note and whether the series’ creators were able to come up with a solid enough plot for another six hours of narrative. In this respect, the first episode, despite its high degree of suspense, comes off mainly as an effort to kill some time and it doesn’t tell us much about what will happen next or whether there is a reason to look forward to it other than the great directing, actors and bold feminist subtext (which is actually not negligible).

George Carlin: Back In Town (1996) (Fernsehfilm)

“Not every ejaculation deserves a name.” No emitting of test farts. The nearly 60-year-old Carlin quite quickly gets to the point as he takes shots at anti-abortion conservatives immediately upon taking the stage at the Beacon Theater in New York. Without pausing or hesitating, he follows up with a fitting insult of Catholics (God has been one of the main causes of death for centuries) and a radical rejection of the “self-serving bullshit story” about the sanctity of life (the dead don’t give a fuck). The cadence of his jokes is lethal and his indifference to political correctness is irresistible. Though I do not fully identify with Carlin’s totally nihilistic “fuck everybody” view of the world, I never for a moment stopped admiring his ability to make his anger at Mickey Mouse, motivational books, ugly kids in home videos and fat yuppie baby boomers so amusing, and how deeply he could cut with the punchlines of his dirty and outwardly autotelic jokes (“Just like now!”). What is no less admirable is the fact that most of his observations remain valid even twenty years later (just substitute smartphones for video cameras). If any stand-up special deserves to be called a “classic”, it’s definitely this one.

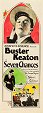

Sieben Chancen (1925)

This time the natural disaster with which many of Keaton’s films culminate takes the form of approximately five hundred angry women in wedding dresses chasing the protagonist through the streets of Los Angeles. The brilliantly intensified, breakneck stunts and off-the-wall jokes (a turtle!) drive the twenty-minute chase forward, culminating in a scene that leaves the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark in the dust, preceded by a wonderful example of working with time limits. Keaton plays a bachelor who can inherit seven million dollars if he gets married no later than seven o’clock in the evening on his twenty-seventh birthday. That day has arrived and there are only a few hours left until evening. After a girl with whom he has long secretly been in love rejects him because of an inappropriate remark, he tries his luck with seven other ladies. With each rejection, the fateful seventh hour draws closer and Frigo, who keeps a straight face even as he zigzags between rolling boulders, must not stop if he doesn’t want to lose his race against time. Thanks to that, Seven Chances is an extremely dynamic film, enlivened by clever visual gags (which don’t draw too much attention to themselves and leave it up to you to find and appreciate them) in addition to the ceaseless movement of the protagonist, the unconventional design of some scenes (the “static” relocation by car) and the multiple actions running in parallel (the black servant, obviously played a white actor in blackface, is also an unpleasant reminder of the racism of the period in which the film was made). As befits a film of movement, the greatest risk is stopping – the situation becomes critical after the protagonist’s brief nap in the church. Unlike Chaplin’s more traditionalist farces, in which finding a partner also means finding harmony, in Keaton’s film, getting married is essentially a pragmatic decision (or rather a necessity) that is, furthermore, preceded by a series of stressful and life-threatening events. Therefore, the romance of the last shot must necessarily be disrupted by an annoying dog, thus giving us the feeling that no great idyll awaits the newly married couple anyway. 85%

Café Society (2016)

“Where's character? Where's loyalty?” The protagonist's father asks the right questions. In Woody Allen’s new film, you won’t find multi-dimensional characters that behave toward each other with any degree of loyalty. You will also search in vain for humour (a few amusing lines merely recycle what we have already heard in Allen’s films, but in funnier versions), compositional motivation for a number of scenes (such as the opening scene with a prostitute), type-appropriate casting (only Steve Carrel with his parted hair is more or less suitable for the 1930s setting), meaningful involvement of an omniscient narrator (is it really necessary to describe absolutely everything, even the beauty of the sunrise that we are just looking at?), any sign that the plot is leading to something (in fact, the story could just go on and on in cycles until the characters get old and die), or any reason that the story is set in the era of classic Hollywood. Well, any reason other than the fact that Woody simply loves this period and until someone builds a time machine, the only way to return to it is through movies. Rather than the need to tell an engaging story and share an original idea, it seems that love for the depicted period and setting was the main (or perhaps even the only) motivation for making Café Society. Thanks to Vittorio Storaro’s cinematography, the film looks beautiful. The abundance of light and a golden hue give the shots a supernatural charm and it is clear that we are in a world where dreams are born. Populate this world with characters who constantly blabber on about famous actors, actresses and directors (and they blabber only not to be quiet – the point and main purpose of the dialogue is simply for us to hear a familiar name), add a jazz soundtrack and you have a film. Actually, no, you don’t, because it is still necessary to at least somehow connect the individual scenes with the most lackluster romance under the sun, even if you really don’t care about the people involved in that romance because they rather prevent you from enjoying the period costumes, architecture and set decorations (based on which the lead roles were written – two self-satisfied characters defined only by the fact that they want to go to the movies and are unable to make independent grown-up decisions). Café Society is such a soul-crushing case of total directorial and screenwriting laxity that if it weren’t for the higher production values and a few well-known actors, I would think that this is the first attempt by a not very good writer who doesn’t understand that telling a story with pictures is not the same as telling a story with words. Looking at it from a more generous angle, it is significantly more likely that Allen’s first series (Crisis in Six Scenes) will be far more entertaining than his (so far) last film. The consolation to be found in that, however, is as comparably worthless as Café Society itself. 40%